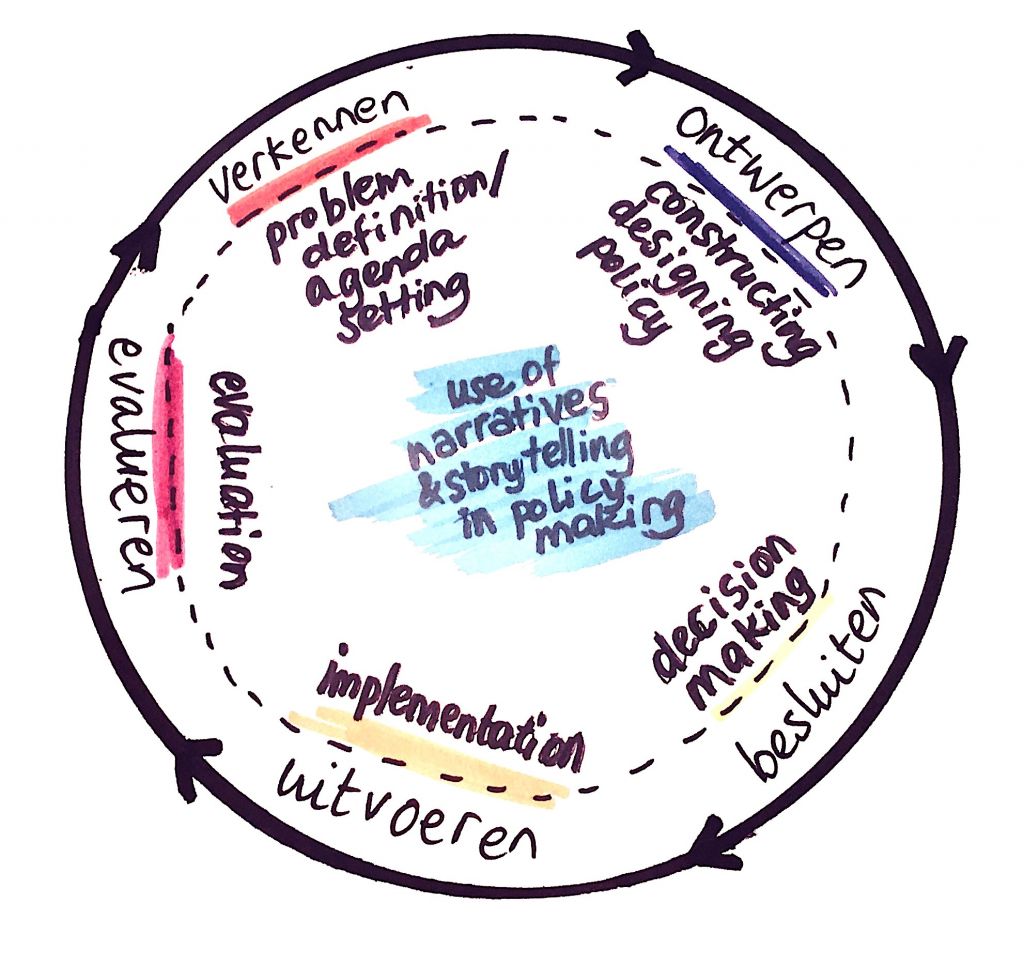

The impact of stories. How to translate stories of lived experience to the policy cycle?

What is the impact of stories? How can user’s stories be translated into policy in such a way that they contribute visibly to policy design and – evaluation? These questions were at the heart of the first conference of the Knowledge Network for Narrative Accountability on 2 March 2020 in Utrecht. 80 policymakers, social professionals, researchers and also storytelling specialists came together in Utrecht to exchange experience and knowledge related to the use of narrative tools in the field of social interventions and – policy making. The conversations shed extra light on the processes of co-creation and innovation of democratic processes in local governance and administration.

Mapping of narratives

At 8 discussion tables, participants exchanged experiences about the use of narrative approaches and stories in the different stages of the policy cycle. What makes narrative approaches attractive tools in policy making? And what are the positive and negative sides of it? Another cluster of questions would deal with the skills necessary to work with narratives and its effect on the working processes for instance on civil servants? The last issue dealt with a prospect about the future: how could narrative ways of working be embedded in the system?

From the conversations, we learnt that participants find it important to work with stories of lived experience and in dialogue with each other. Social professionals and civil servants were willing to change their habits and change the system, too much oriented on financial and economic targets and cost-benefit analysis and less on the actual needs of citizens. However, participants could not picture yet how individual stories they hear and experience could lead to a common vision and in the end to new policy in which users would feel heard and recognized.

Narrative interventions and co-creation

Suzanne Tesselaar, a specialist in stories and change, gave us valuable insights. She simply stated that gathering and listening to stories should be organized as a narrative intervention. In fact, having shared the stories, all stakeholders should be invited to make sense of the stories told. From that point, common meaning will lead to a common story of a problem or a situation, which will be the basis for common analysis and drafting of common future policy. This is in line with our own experience in CoSIE with the use of community reporting via People’s Voice Media, common analysis of stories followed by the organization of conversations of change. This way of working gave us new insights into the possibilities for innovation in public services involving all stakeholders.

Towards a narrative democracy…

It is not easy to integrate narrative and co-creative approaches into the present system. Public administrations and most organizations work with plans and targets defined beforehand based on prospects. Available resources, time and money constitute a well-defined and determined frame. Working with narratives and involving people requires the time needed for such a process. Often this does not correspond to planned time. It is also important that decision makers provide for space to integrate open outcomes and unexpected solutions. These do not always correspond to the budgetary lines and organizational structure of local administrations.

However, in line with the work of Pierre Rosanvallon, these new ways of working are signs of democratic change. He observes a general need for ‘Narrative Democracy’, as he calls it. We need to go back to basics and listen to the stories of those who are not visible, those whose voices are not heard. Through the sharing of stories a new common understanding of what living together actually means. Only in this way can political representatives regain trust from their citizens. Democratic systems are not static structures. Democracy can never be achieved: it is an ongoing process. It needs to adapt to major, current social transformation time. We need new democratic foundations, based on the stories of all and not only of the powerful. This is why our project on co-creation and innovation of public services matters. It strives to lend voice to those who are not heard.

The knowledge network for narrative accountability (KNV) was set up in 2018 as a hybrid and innovative network organization, in which research institutes, municipalities, social care organizations, social entrepreneurs and citizen representatives work together. The objective is to develop a common way to develop narrative accountability in practice, to evaluate narrative approaches and assess them on their effective usage in all stages of the policy cycle in local government settings.

Recommendations on the use of narratives in policy cycle stages

- Agree upon common values and working principles by all key figures.

- Common understanding of meaning of narrative working for working processes.

During the narrative process with citizens or clients:

- Anticipate stagnation and start with a common agreement about the basic principles of narrative working.

- Create shared ownership for the narrative process to be engaged.

- All stories and point of views matter and are equally important.

- Adapt language, image, form of conversations to the participants involved. Use visuals, art forms if necessary.

- Everyone should be able to contribute and understand what it is about.

- Time and space to let the process evolve.

- Define open goals instead of measurable targets.

Writer: Dr. Sandra Geelhoed, HU University of Applied Sciences